Germany: Returning Home

When we travel it is difficult to know what will stay with us when we come home and pick up the threads of our daily life. Once the photos have been posted (gone are the slide shows in a darkened room over cocktails and cheese balls), we simply move on. And as you know, not much makes it on to this blog unless I am particularly moved by an experience and it can provide a skewed postmark to what may have been actually much more of a whole cloth journey than it appears (with a thankful nod to our wonderful hosts in Germany, who gave us the trip of a lifetime). But I don't know how to go about it in any different way and in some ways this space is all I will have when most memories have vanished. I need to keep this in mind.

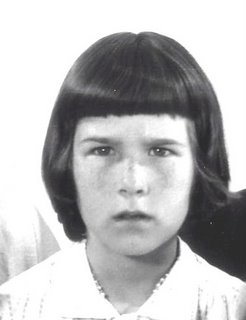

Fact is, I do not have a very good memory for certain details and rely on others for this Herculean accomplishment. Each period in my life has a memory keeper in the form of a friend or a sibling: For example, I have forgotten almost everything that happened when I was in theatre school, that crazy emotionally-charged wild ride through the machinations of our still-immature brains. Most of it should be buried as it was a constant assault on my ego and not pretty given how fragile I was when I started there. But I do recall certain events, mostly cringe-worthy, as we lived fully vulnerable in the daunting and critical eye of our teachers who were pushing us to dig into our interior worlds and pull out everything usable for the sake of authenticating our performances. My memory of these times is limited to a collection of snapshots, among them: trying not to giggle as I examined, upside down, the face of my new friend Sally in a classroom exercise. Doing a sense-memory exercise (God, there were endless versions of these) with blindfolds on and our hands in a variety of food substances which we put in our mouths and savored. Lying on the carpeted floor and breathing with our diaphragms, one of the few things that stayed with me to this day. Singing lessons when I discovered my voice had gone from an alto to a high soprano. Performing Dylan Thomas' poem, "Do not go gentle into that good night. Rage, rage against the dying of the light...." in a darkened room, listening to others do it better....damnation! Sitting in the school lounge reading bits of Margaret Atwater's poetry, releasing my feminist wings as delicate as those of a dragonfly because we were already equal were we not? There was the prickly stiffness of the starched fabric of my costume as Sonya in Uncle Vanya, one of my only good performances near the end of school term. And boys, of course, especially the one who was way out of my league that I pined after, and the one who became famous, the boyfriend who farted in bed at night and left me thinking that this relationship thing was not what I'd imagined it to be.

I can conjure up a a good number more of these bits and pieces, but when it comes to specifics, my friend Sally is the one I turn to. She remembers the names of our schoolmates, my boyfriends, the color of the princess phone in our attic kitchen, the people who lived in the flat below us, and the names of our landlords. My sister Deb does the same for our childhood memories, and it isn't often I take her on when it comes to those facts and figures because I will certainly be wrong in almost every case.

So when I look at the piece I first wrote about Germany and the connection with the past wars which engaged our countries I cannot help but wonder why it was the initial post-card. Why not the breathtaking landscape that we hiked in, the sharpness of the air, clean and unencumbered by city and smog, the winding paths to castles shrouded in mist, the horse-drawn wagon that lumbered up the path, nostrils steaming? In Lake Titisee in the Black Forest where cuckoo clocks are made by hand, I spent an entire morning studying them in all their variations, admiring the extraordinary workmanship of intricately carved wood and the movements of little people chopping wood or dancing, waterfalls with real water, cuckoos that made all manner of entrances and sounds. The rest of my family, along with a very patient Christine, left me alone to immerse myself for so long even the sales girl gave up. I finally made a decision, and wondered then where I would put this piece of art, a little kitchy and certainly with more personality than a clock deserved to have, but I didn't care. I had snapped off the branch of a tree in this forest and I wanted to bring it home. A cuckoo clock, chiming as it does every hour, making a group of merrymaking dancers swirl to the rhythm of a minute hand, will certainly not let me forget. I want to put it over the kitchen sink where I will see and hear it every day as it's the second busiest room in the house and certainly the friendliest.

I have my photographs too, and the memory of exploring winding cobblestone streets in three different languages, all within a short distance of our base in Freiburg, with people whose company and conversation I happily soaked in over steaming cups of dark chocolate and shared pastries. Part of the joy as a traveller is hands-on experiencing things that are passing through the centuries untethered to us, knowing they will flow on to an infinite future. I think that's why we travel, to engage on a grander scale and perhaps become larger in the moment because of it. And on a personal level, the most memorable trips are also about the essence of the more ephemeral aspects of the journey, the things we do not expect, the moments of deep connection that provide a more complete understanding of our human nature, seen through a different lens. But it does involve other people, and that's a risk.

If we are open to it, sometimes traveling takes us places we cannot foresee. And sometimes our memories fade until only the essence remains. I'm going to keep writing until the whole picture is revealed.

Fact is, I do not have a very good memory for certain details and rely on others for this Herculean accomplishment. Each period in my life has a memory keeper in the form of a friend or a sibling: For example, I have forgotten almost everything that happened when I was in theatre school, that crazy emotionally-charged wild ride through the machinations of our still-immature brains. Most of it should be buried as it was a constant assault on my ego and not pretty given how fragile I was when I started there. But I do recall certain events, mostly cringe-worthy, as we lived fully vulnerable in the daunting and critical eye of our teachers who were pushing us to dig into our interior worlds and pull out everything usable for the sake of authenticating our performances. My memory of these times is limited to a collection of snapshots, among them: trying not to giggle as I examined, upside down, the face of my new friend Sally in a classroom exercise. Doing a sense-memory exercise (God, there were endless versions of these) with blindfolds on and our hands in a variety of food substances which we put in our mouths and savored. Lying on the carpeted floor and breathing with our diaphragms, one of the few things that stayed with me to this day. Singing lessons when I discovered my voice had gone from an alto to a high soprano. Performing Dylan Thomas' poem, "Do not go gentle into that good night. Rage, rage against the dying of the light...." in a darkened room, listening to others do it better....damnation! Sitting in the school lounge reading bits of Margaret Atwater's poetry, releasing my feminist wings as delicate as those of a dragonfly because we were already equal were we not? There was the prickly stiffness of the starched fabric of my costume as Sonya in Uncle Vanya, one of my only good performances near the end of school term. And boys, of course, especially the one who was way out of my league that I pined after, and the one who became famous, the boyfriend who farted in bed at night and left me thinking that this relationship thing was not what I'd imagined it to be.

I can conjure up a a good number more of these bits and pieces, but when it comes to specifics, my friend Sally is the one I turn to. She remembers the names of our schoolmates, my boyfriends, the color of the princess phone in our attic kitchen, the people who lived in the flat below us, and the names of our landlords. My sister Deb does the same for our childhood memories, and it isn't often I take her on when it comes to those facts and figures because I will certainly be wrong in almost every case.

So when I look at the piece I first wrote about Germany and the connection with the past wars which engaged our countries I cannot help but wonder why it was the initial post-card. Why not the breathtaking landscape that we hiked in, the sharpness of the air, clean and unencumbered by city and smog, the winding paths to castles shrouded in mist, the horse-drawn wagon that lumbered up the path, nostrils steaming? In Lake Titisee in the Black Forest where cuckoo clocks are made by hand, I spent an entire morning studying them in all their variations, admiring the extraordinary workmanship of intricately carved wood and the movements of little people chopping wood or dancing, waterfalls with real water, cuckoos that made all manner of entrances and sounds. The rest of my family, along with a very patient Christine, left me alone to immerse myself for so long even the sales girl gave up. I finally made a decision, and wondered then where I would put this piece of art, a little kitchy and certainly with more personality than a clock deserved to have, but I didn't care. I had snapped off the branch of a tree in this forest and I wanted to bring it home. A cuckoo clock, chiming as it does every hour, making a group of merrymaking dancers swirl to the rhythm of a minute hand, will certainly not let me forget. I want to put it over the kitchen sink where I will see and hear it every day as it's the second busiest room in the house and certainly the friendliest.

I have my photographs too, and the memory of exploring winding cobblestone streets in three different languages, all within a short distance of our base in Freiburg, with people whose company and conversation I happily soaked in over steaming cups of dark chocolate and shared pastries. Part of the joy as a traveller is hands-on experiencing things that are passing through the centuries untethered to us, knowing they will flow on to an infinite future. I think that's why we travel, to engage on a grander scale and perhaps become larger in the moment because of it. And on a personal level, the most memorable trips are also about the essence of the more ephemeral aspects of the journey, the things we do not expect, the moments of deep connection that provide a more complete understanding of our human nature, seen through a different lens. But it does involve other people, and that's a risk.

If we are open to it, sometimes traveling takes us places we cannot foresee. And sometimes our memories fade until only the essence remains. I'm going to keep writing until the whole picture is revealed.