London Papyrus

My time in London was short and focused on gathering research on Margaret Forde. The public records office of Northern Ireland (PRONI) in Belfast yielded precious little: A letter from Margaret's husband, and older Mathew to his son, on microfilm, and tangential references to the family, but not much else. There were many references to the Fordes in the massive Abercorn collection because Margaret's family came from a long line of this Earldom. For those interested knowing more about the Abercorns, now a Dukedom which survives and still remains intertwined socially with the Fordes to this day, here's a link:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Duke_of_Abercorn

One gem I did find at PRONI was Margaret and Mathew's 1670's original marriage settlement, a giant piece of supple vellum, very thin calfskin which was the choice for all legal documents and proved to be quite durable, pliable, preserving ink better than anything on paper. The vellum documents in the Forde's collection were in excellent shape, but unfortunately this one at PRONI was in such degraded condition I didn't dare unfold it more than to view the top of the document, and even then, bits of musty brown pieces flaked off. The box was damp, and the reference title mis-labled (the date was incorrect) and it was disappointing to think PRONI couldn't do better. But to their credit when I brought the document up to the archive assistants they promised it would be taken to the manuscript restoration team for evaluation.

The marriage settlement, which outlined the dowry offered from the bride's family to the future husband and an allotment provided by the father of the groom (an exchange of money and property that only involved the men as was the custom) was the closest I came in Ireland to touching something that my ancestor had put her hands on. There is no substitute for this kind of continuum, and thrilling to think that the DNA from her resting arm as she carefully signed her name to the document was mingling with mine as I gently swept my finger across it.

But there was a promise of more in London that kept me going. The current Forde heir told me he'd seen a letter from Margaret to her sister, but when I registered at the front desk of the British Library and obtained my mandatory reader's card, there seemed to be no mention of this or any other document referencing the Fordes in the searchable database. Discouraged, I mentioned this to the people at the reception desk, and one of them said he actually remembered the letter from when he'd been working in the manuscript department. Quite a lucky coincidence given my few days there. More importantly he cautioned the letters were not located under the Forde name but in a subset under a different author.

If it hadn't been for this friendly staffer, I might not have been as persistent with the archivist in the manuscripts department who eventually located some of the letters. Although the elusive Margaret Forde item wasn't there, I did find a series of letters to one of her sons, from husband Mathew, and sister, Lu. During this time period it became obvious by the tone of the father's letters that Mathew II had ditched his university education and was hanging out with his other 'gentlemen' friends doing pretty much nothing except lounging in his club, eating well, and playing cards. His father, who was experiencing scant revenues from his tenants due to various skirmishes between the Catholics and the Protestants in Ireland, was feeling the pinch of his son's debts in London.

The letter that most interested me though, was from his sister Lu, because the desperation in her pleas to a wayward brother was evident in the tiny but meticulous script that covered every available inch, and sideways on the margins - faded but still readable on the square of linen paper bearing the fold marks from it's original small square shape sealed with wax as was the custom. It was a true window into the language, culture, and humor of the day.

I've excerpted a small sample here, with highlights. Many words are spelled differently and are not errors. I've included some of the old words, but I've reconstituted some of the contractions that make it difficult to understand (i.e. y(r) is 'your' and y(u) is 'you') 'ye' is used interchangeably for 'you' and 'the' but should be clear in the context of the sentence. I also added some punctuation because, as I mentioned in an earlier post, they don't use it and it can be damnably hard to understand in its absence:

To: Mathew Forde, Esq

The Golden Cup, Covent Garden

September 12, 1695

I am very sorry to find, my Dear Brother, so uncharitable as not to comfort his poor sisters in affliction, for I assure you we were never in more need of it, your time, your attention, and your greatest satisfaction we are capeable of receiving would be to hear often from you. .....I have been a great while in debate whether I should write to you or not, but my good nature has got the better so last night I was much afraid I could not have brought myself to stoop soe low but I find great misfortunes like mine humbles one mightily as well as ye pleasures of London make you take apon yerself. But when I consider yet you have to write but once to our faire kindred in Dublin yet (we) are so deserving. I don't much wonder yet you should not think of a country girle, you may venture to call me for I am in despaire of going to Dublin before I see you. Your honor we have lately acquired has disappointed us of our expectations.

(she goes on this vein for another 30 lines before finally getting off on to another topic)

As for news, you don't deserve I should send you any, nor indeed I have not much at this time. We have been very dull ever since ye parliament for it has taken away most of our fine sparks as we have a very great want of my Lord Anglissy as he used to furnish us with all ye diverting news of London. I suppose you know of all ye weddings yet has been in Dublin so I will only give you an account of one we are like to have here in our neighborhood. It is between Mally Masterson and one Mr. Wise, who is very far from being (a gentleman like you) but he has 7 hundred a year and ye thing was proposed by his friends before the young couple saw one another and there was no great love in ye case. He came to see us the other day and we were sent for to give our opinion of him but I never saw anything more comical. He never was in Dublin but once, but had the good fortune of meeting with an extraordinary dancing master, whom he lives for, and he could not rest till he then takes part in dancing a minuet which he did with his girl and ye company burst out laughing and they were forced to break off in ye middle of ye dance with the poor lover who was very sorry but had not the sense to take it all in. I could say a great deal of him but fearing I have bored you already.

I must now bid you adieu assuring you I am, Dr Brother, your affectionate sister Lu.

My sister is so gerry with you yet she wishes me to say nothing for her poor George is going to Dublin to be flux'd for his eye. Mr. Dawson and Mr. Carr bid me to give their service to you and tell you they have a very great want of ye at ye Tavern where you used to meet.

Eventually Mathew III came to his senses and returned to Dublin to take over his father's estate, and also stood for parliament in Dublin. But later correspondence with this father (who by then was in better financial straits), showed he was still a bit of a spendthrift as he wanted to enlarge the house in Seaforde (possibly a 'shooting box', a smaller mansion used for hunting season as the main estate was south of Dublin) and his father cautioned him to scale back the project, and to be cautious with the equally ambitious architect. These renovations were never made, and the house was destroyed by fire in the early 19th Century. The current house was rebuilt shortly thereafter.

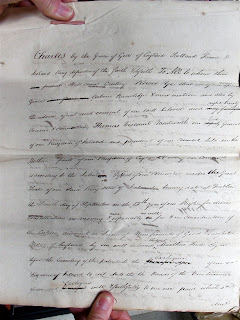

Below is a sample of a legal document from the 17th Century on vellum (this one is actually a handwritten copy of the original made by the solicitor because of its importance). As this one, from a private collection, was several pages long it was bound with a large 'staple' top left made of something that looks like cat gut (flexible but strong). All documents carried various coats-of-arms wax seals of the parties involved attached to tiny vellum tags at the bottom, and other seals as required if it was folded and secured for privacy.

Documents at PRONI and the British Museum could not be photographed nor photocopied, so I had to transcribe them all by hand.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Duke_of_Abercorn

One gem I did find at PRONI was Margaret and Mathew's 1670's original marriage settlement, a giant piece of supple vellum, very thin calfskin which was the choice for all legal documents and proved to be quite durable, pliable, preserving ink better than anything on paper. The vellum documents in the Forde's collection were in excellent shape, but unfortunately this one at PRONI was in such degraded condition I didn't dare unfold it more than to view the top of the document, and even then, bits of musty brown pieces flaked off. The box was damp, and the reference title mis-labled (the date was incorrect) and it was disappointing to think PRONI couldn't do better. But to their credit when I brought the document up to the archive assistants they promised it would be taken to the manuscript restoration team for evaluation.

The marriage settlement, which outlined the dowry offered from the bride's family to the future husband and an allotment provided by the father of the groom (an exchange of money and property that only involved the men as was the custom) was the closest I came in Ireland to touching something that my ancestor had put her hands on. There is no substitute for this kind of continuum, and thrilling to think that the DNA from her resting arm as she carefully signed her name to the document was mingling with mine as I gently swept my finger across it.

But there was a promise of more in London that kept me going. The current Forde heir told me he'd seen a letter from Margaret to her sister, but when I registered at the front desk of the British Library and obtained my mandatory reader's card, there seemed to be no mention of this or any other document referencing the Fordes in the searchable database. Discouraged, I mentioned this to the people at the reception desk, and one of them said he actually remembered the letter from when he'd been working in the manuscript department. Quite a lucky coincidence given my few days there. More importantly he cautioned the letters were not located under the Forde name but in a subset under a different author.

If it hadn't been for this friendly staffer, I might not have been as persistent with the archivist in the manuscripts department who eventually located some of the letters. Although the elusive Margaret Forde item wasn't there, I did find a series of letters to one of her sons, from husband Mathew, and sister, Lu. During this time period it became obvious by the tone of the father's letters that Mathew II had ditched his university education and was hanging out with his other 'gentlemen' friends doing pretty much nothing except lounging in his club, eating well, and playing cards. His father, who was experiencing scant revenues from his tenants due to various skirmishes between the Catholics and the Protestants in Ireland, was feeling the pinch of his son's debts in London.

The letter that most interested me though, was from his sister Lu, because the desperation in her pleas to a wayward brother was evident in the tiny but meticulous script that covered every available inch, and sideways on the margins - faded but still readable on the square of linen paper bearing the fold marks from it's original small square shape sealed with wax as was the custom. It was a true window into the language, culture, and humor of the day.

I've excerpted a small sample here, with highlights. Many words are spelled differently and are not errors. I've included some of the old words, but I've reconstituted some of the contractions that make it difficult to understand (i.e. y(r) is 'your' and y(u) is 'you') 'ye' is used interchangeably for 'you' and 'the' but should be clear in the context of the sentence. I also added some punctuation because, as I mentioned in an earlier post, they don't use it and it can be damnably hard to understand in its absence:

To: Mathew Forde, Esq

The Golden Cup, Covent Garden

September 12, 1695

I am very sorry to find, my Dear Brother, so uncharitable as not to comfort his poor sisters in affliction, for I assure you we were never in more need of it, your time, your attention, and your greatest satisfaction we are capeable of receiving would be to hear often from you. .....I have been a great while in debate whether I should write to you or not, but my good nature has got the better so last night I was much afraid I could not have brought myself to stoop soe low but I find great misfortunes like mine humbles one mightily as well as ye pleasures of London make you take apon yerself. But when I consider yet you have to write but once to our faire kindred in Dublin yet (we) are so deserving. I don't much wonder yet you should not think of a country girle, you may venture to call me for I am in despaire of going to Dublin before I see you. Your honor we have lately acquired has disappointed us of our expectations.

(she goes on this vein for another 30 lines before finally getting off on to another topic)

As for news, you don't deserve I should send you any, nor indeed I have not much at this time. We have been very dull ever since ye parliament for it has taken away most of our fine sparks as we have a very great want of my Lord Anglissy as he used to furnish us with all ye diverting news of London. I suppose you know of all ye weddings yet has been in Dublin so I will only give you an account of one we are like to have here in our neighborhood. It is between Mally Masterson and one Mr. Wise, who is very far from being (a gentleman like you) but he has 7 hundred a year and ye thing was proposed by his friends before the young couple saw one another and there was no great love in ye case. He came to see us the other day and we were sent for to give our opinion of him but I never saw anything more comical. He never was in Dublin but once, but had the good fortune of meeting with an extraordinary dancing master, whom he lives for, and he could not rest till he then takes part in dancing a minuet which he did with his girl and ye company burst out laughing and they were forced to break off in ye middle of ye dance with the poor lover who was very sorry but had not the sense to take it all in. I could say a great deal of him but fearing I have bored you already.

I must now bid you adieu assuring you I am, Dr Brother, your affectionate sister Lu.

My sister is so gerry with you yet she wishes me to say nothing for her poor George is going to Dublin to be flux'd for his eye. Mr. Dawson and Mr. Carr bid me to give their service to you and tell you they have a very great want of ye at ye Tavern where you used to meet.

Eventually Mathew III came to his senses and returned to Dublin to take over his father's estate, and also stood for parliament in Dublin. But later correspondence with this father (who by then was in better financial straits), showed he was still a bit of a spendthrift as he wanted to enlarge the house in Seaforde (possibly a 'shooting box', a smaller mansion used for hunting season as the main estate was south of Dublin) and his father cautioned him to scale back the project, and to be cautious with the equally ambitious architect. These renovations were never made, and the house was destroyed by fire in the early 19th Century. The current house was rebuilt shortly thereafter.

Below is a sample of a legal document from the 17th Century on vellum (this one is actually a handwritten copy of the original made by the solicitor because of its importance). As this one, from a private collection, was several pages long it was bound with a large 'staple' top left made of something that looks like cat gut (flexible but strong). All documents carried various coats-of-arms wax seals of the parties involved attached to tiny vellum tags at the bottom, and other seals as required if it was folded and secured for privacy.

Documents at PRONI and the British Museum could not be photographed nor photocopied, so I had to transcribe them all by hand.

I may not yet have put my hands on a letter from Margaret Forde, but these other snippets are equally valuable as they illuminate both the differences in our time, and the similarities of human nature, which changes much more slowly. Probably much more slowly than we would like to admit, as the answer to conflicts seem as quixotic as ever. Women in love. Marriages of convenience. Wayward sons. Religious & Ethnic War.

Something quite rich to mull about as I start working on the framework for the new novel.