XIV: Tom

In 1985 when Tom was born his picture was published in the Star. “Record-size baby welcomed in Toronto General!” the caption read. He was a hefty fourteen pounds with a barrel chest and huge feet. And because he’d been carried to term in the heat of a particularly sweltering summer by a woman who was thirty-nine and reluctantly pregnant, he was also bad tempered from the get-go. His full-lung squall dubbed ‘the rebel yell’ by Delys could be heard down the block even when all the windows were shut (which they frequently were to keep family matters private) and he cried more hours than he was silent.

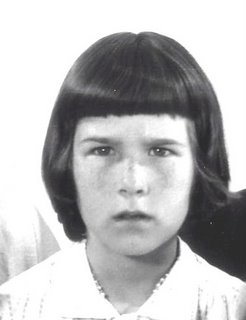

Sara, who was five at the time, found the silence to be worse because Tom’s infrequent moments of reflection seemed to be focused on her and the stares became more aggressive with time. She began to believe, fueled by her father’s imagination stories at bedtime about monsters emerging from dark places to eat little children, it was not impossible her brother was a changeling, and that his stare was far too intelligent for his infantile status. She wondered what he got up to in the dark hours of the night when he slept behind locked doors, locked only after he’d been found one afternoon stripped of his diaper and taking a casual pee in the neighbor’s prize azelea bushes.

As a baby Tom had a definite size advantage, with a low center of gravity that made him a force to be reckoned with once he got some speed up. This was how Sara, who should have known better than to be on the flat roof of the garage behind Notty’s apartment, had come to be cannonballed into the abyss by her brother, who was then barely three. She had been standing near the edge looking at a particularly high snowdrift (and thankfully clad in a bulky snowsuit) when Tom somehow slipped his harness and had run at her full stop. She’d barely turned when he caught her at the waist and before she could right herself she’d gone head over heels. She remembered even now how surreal it had been, and in her memory the fall had been more like a gentle drift downwards followed by a very soft landing into the new snow. But in truth she must have had the wind knocked out of her for she’d lain there for a quite a while half buried, until Tom, who had played on the roof (in considerably more danger given his size) for over a quarter of an hour, finally wandered to Notty’s back door with his announcement.

“Ganma, Ganma, she falled off the roof!”

But his size advantage mysteriously evened out by the time he was five and much to his chagrin he no longer towered over his playmates which meant his bullying tactics were not as effective. The first time he was slapped back by a fiery little redhead he ran straight to Delys and when met with little sympathy changed tactics and focused his attentions Sara who seemed both bewildered by and a little afraid of him. He found it quite amusing to torment her when they were alone, beginning with crude devices (picking his nose and flinging at her was an early favorite) and then graduating to more subtle forms of torture. Unlike most siblings who exercised power based on birth order, Tom-the-younger had the edge almost from the day he was born and he never conceded the advantage.

Delys seemed unaware of the danger brewing between her two young ones, busy as she was trying to shore up her failing interior decorating business. She blamed the demise of “Done by Delys” on the birth of her children and at one point was so overwhelmed that her alarmed husband had hired a nanny. Sara remembered the woman well, she had come advertised as the grandmother-type but when free of Delys’ oversight her pale blue eyes hardened into steel and both children feared her grip and her tongue, which lashed out at unexpected moments and kept them servile. It wasn’t until Tom had kicked a grapefruit size welt into her thigh that she’d packed her bags in a huff and scrubbed out. It was the only thing Sara had ever been grateful to Tom for.

Notty was watching Sara at the table. Even in the steamy warmth of the kitchen, Sara held onto herself as if to preserve body heat. Her legs were too skinny, she thought. And the hair….

“Bubala…”

Sara shook her head. She knew what was coming. Notty sighed and turned to the cooling confection. She put down a yard of wax paper and began dropping spoonfuls of caramelized brown sugar mixed with pecans and candied popcorn into neat rows. When the first batch had cooled she put a few on well-worn Staffordshire saucer. Sara had once asked about the Blue Willow pattern, with its ornate Chinese landscape in which two doves cavorted while men toiled in the fields below. She’d asked about the doves and Notty had told her the pattern was based on an ancient Mandarin story about two ill-fated lovers who had perished and been reborn.

As a teenager she learned more of the story and discovered that they had been murdered, burned alive in their home by the father who felt the young man unworthy of his daughter.

“Some people are just not meant to be together,” Notty had said to her.

And a few months later her father, whom she’d worshipped for his patience, his courage, and his intelligence, had disappeared and taken her brother with him.

Sara, who was five at the time, found the silence to be worse because Tom’s infrequent moments of reflection seemed to be focused on her and the stares became more aggressive with time. She began to believe, fueled by her father’s imagination stories at bedtime about monsters emerging from dark places to eat little children, it was not impossible her brother was a changeling, and that his stare was far too intelligent for his infantile status. She wondered what he got up to in the dark hours of the night when he slept behind locked doors, locked only after he’d been found one afternoon stripped of his diaper and taking a casual pee in the neighbor’s prize azelea bushes.

As a baby Tom had a definite size advantage, with a low center of gravity that made him a force to be reckoned with once he got some speed up. This was how Sara, who should have known better than to be on the flat roof of the garage behind Notty’s apartment, had come to be cannonballed into the abyss by her brother, who was then barely three. She had been standing near the edge looking at a particularly high snowdrift (and thankfully clad in a bulky snowsuit) when Tom somehow slipped his harness and had run at her full stop. She’d barely turned when he caught her at the waist and before she could right herself she’d gone head over heels. She remembered even now how surreal it had been, and in her memory the fall had been more like a gentle drift downwards followed by a very soft landing into the new snow. But in truth she must have had the wind knocked out of her for she’d lain there for a quite a while half buried, until Tom, who had played on the roof (in considerably more danger given his size) for over a quarter of an hour, finally wandered to Notty’s back door with his announcement.

“Ganma, Ganma, she falled off the roof!”

But his size advantage mysteriously evened out by the time he was five and much to his chagrin he no longer towered over his playmates which meant his bullying tactics were not as effective. The first time he was slapped back by a fiery little redhead he ran straight to Delys and when met with little sympathy changed tactics and focused his attentions Sara who seemed both bewildered by and a little afraid of him. He found it quite amusing to torment her when they were alone, beginning with crude devices (picking his nose and flinging at her was an early favorite) and then graduating to more subtle forms of torture. Unlike most siblings who exercised power based on birth order, Tom-the-younger had the edge almost from the day he was born and he never conceded the advantage.

Delys seemed unaware of the danger brewing between her two young ones, busy as she was trying to shore up her failing interior decorating business. She blamed the demise of “Done by Delys” on the birth of her children and at one point was so overwhelmed that her alarmed husband had hired a nanny. Sara remembered the woman well, she had come advertised as the grandmother-type but when free of Delys’ oversight her pale blue eyes hardened into steel and both children feared her grip and her tongue, which lashed out at unexpected moments and kept them servile. It wasn’t until Tom had kicked a grapefruit size welt into her thigh that she’d packed her bags in a huff and scrubbed out. It was the only thing Sara had ever been grateful to Tom for.

Notty was watching Sara at the table. Even in the steamy warmth of the kitchen, Sara held onto herself as if to preserve body heat. Her legs were too skinny, she thought. And the hair….

“Bubala…”

Sara shook her head. She knew what was coming. Notty sighed and turned to the cooling confection. She put down a yard of wax paper and began dropping spoonfuls of caramelized brown sugar mixed with pecans and candied popcorn into neat rows. When the first batch had cooled she put a few on well-worn Staffordshire saucer. Sara had once asked about the Blue Willow pattern, with its ornate Chinese landscape in which two doves cavorted while men toiled in the fields below. She’d asked about the doves and Notty had told her the pattern was based on an ancient Mandarin story about two ill-fated lovers who had perished and been reborn.

As a teenager she learned more of the story and discovered that they had been murdered, burned alive in their home by the father who felt the young man unworthy of his daughter.

“Some people are just not meant to be together,” Notty had said to her.

And a few months later her father, whom she’d worshipped for his patience, his courage, and his intelligence, had disappeared and taken her brother with him.

<< Home