The Theory of Big and Small V: False Start

The bitter cold snap was gone by Sunday – a bright, warm kind of day that often came on the heels of winter’s false start. A last gift before bowing to the elements and turning on itself, giving up like a sigh unto death. In the transition time the impermanence of spring-like weather was like forbidden honey, to taste and taste.

And the morning sun had come on strong, turning the night’s freeze into rivulets of fresh water pouring down from glistening roofs and dripping into the sodden earth. The thin layer of snow on the streets had melted into patches of evaporating dampness. Soon all traces of the storm would be gone Sara noted with some satisfaction as she stood at the living room window watching a sparrow (her mother called them ‘little brown jobbies’) peck at something in the damp earth of the rose garden. From the warmth of her bed to the cool darkness of the rest of the house she now felt drawn to the sun, to get out and feel it on her face and arms. A bike ride would do.

Sara had no place to go in particular but after taking Bertie for his morning constitutional she put on a an old pair of corduroys pinched at the ankles by a pair of bike guards, and a hat to guard against the sun. The sky was very blue, washed clean of city soot, the kind of pleasing warmth against a sweater that felt almost like spring. She had a beach bike with thick tires and simple gears. The green paint had long since chipped away but Sara thought the harsh, changeable weather of the city and the constant wind coming off Lake Ontario full of acid rainwater made repainting it a waste of time.

She put her leather satchel in the big wire basket and pushed off, coasting slowly down the long driveway, feet grazing the pavement, thin scarf flying behind. Hands on the handlebars, she looked up and saw the friendlier clouds, the small white ones that had so often taken up her thoughts as she lay under the plumeria bush in the backyard. Her parents, who’d been to Hawaii once on a tour, had bought it home as a seedling and while made it through year after year of winter to grow spreading branches heavy with fragrant blossoms of yellow and cream, they’d told her often of their night at the luau in Wakiki when their host had threaded dozens of these flowers into leis which were put around their necks before the feast began. The way they described it, looking at each other, the pungent aroma that her mother said made her giddy and a little bit ‘fast’. She would laugh then, like Katherine Hepburn, looking heavenward, and her father would always blush.

The plumeria shouldn’t have survived in this cold climate but her mother bagged the huge bush in plastic every winter and then wrapped it in an extra layer of burlap. Then she sprayed a layer of water on it during the first hard frost in January and there it stayed, silent and sleeping, until April when the longer days and warmer weather gradually dried up outer covering and her mother would free it again. The neighbors declared it a marvel.

Sara had never been to Hawaii but her mother had once told her she was not so different from the plumeria. She’d come home from school one afternoon with scratches on her face and arms.

“What happened?” It was a rare day when Delys was home. She was usually down the street taking care of the neighbor’s children. Sara had fled directly into her room and refused to come out.

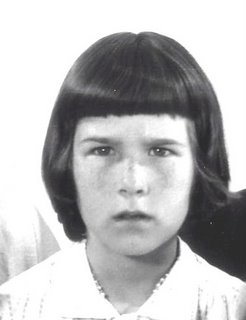

“My bangs aren’t straight!” was all that came muffled through the door after much pleading. When her mother found it unlocked an hour later Sara was sitting on the old wooden vanity, her hair sopping wet flattened under strips of scotch tape across her forehead. She was pressing her palms on her hair, smoothing it down and rocking back and forth.

“What happened!” her mother demanded again, taking her by the shoulders. Sara looked off into the mirror and saw everything in the backwards world. There were so many unexplainable things there. She didn’t understand, but it didn’t stop them from happening. Her mother’s cornsilk hair curled away from her face like a spent dandielion, ready to rise up into the air, like the rest of her. She was all soft and simple. A simpleton. She watched Sara with all the intensity she posessed and still it wasn’t enough to penetrate the density between them.

But she was waiting for an explanation.

“They took me to a closet.” The supply room at the school. The others thought she’d told her teacher about their glue sniffing marathons out by the gymnasium door. The Principal had come for them, there was blood to pay. The girls found a key, pushed her inside and held her up against the wall, clawing at her, stoned and enraged. She didn’t scream. When they were done they left, one by one and she had crept out after them and taken her place in English class as if nothing had happened. They filed in later, defiant and glaring at her. From now on she'd be labled as a snitch.

It was useless to tell her mother any more. She’d long ago stopped trying to cross the divide, to pluck at the strings of her mother’s heart. There were too many children vying for her attention and she’d always said Sara could take care of herself.

“Like water off a duck’s back,” Delys marveled to her friends. “I don’t worry about my Sara!” And then would come the darkness when she complained of the menial jobs she had to take to support them and her spendthrift husband.

But that day her mother had looked hard into her daughter’s eyes and sighed.

“You’re in trouble, aren’t you?” she asked. And she looked off for a while, still holding on to Sara in a protective fashion. Daughter leaned into mother and it was then Delys said,

“You aren’t so different than my plumeria.” Sara didn’t care what she was saying, so lost she was in the embrace. Her mother put her face close to Sara’s lank hair but stopped at putting a hand up to stroke it. “This isn’t your time, she said with resignation, “and you’ve got to cover yourself up and wait for summer to come.” It was then Sara realized just how much drudgery the delicate Hawaiian transplant had been, demanding her mother’s time without mercy, unrepentant. And only Sara to lie under it each flowering spring to breathe in its perfume and dream its dreams.

There was no traffic on the street, dappled as it was from the trees still heavy with fall foliage, the distance beckoned. She set out for unknown territory. Today would be an adventure!

But it was not to be. One turn led to another and she was on the street where Nate lived. She didn’t care if he lived or died. But the house was suddenly there and in the driveway sat a red pick-up truck.

Something new.

She parked her bike on the kickstand and unlatched her pant guards. Shaking out like a dog coming from the rain she made her way up the path and finding the door closed and locked this time, she knocked and waited for someone to let her in.

And the morning sun had come on strong, turning the night’s freeze into rivulets of fresh water pouring down from glistening roofs and dripping into the sodden earth. The thin layer of snow on the streets had melted into patches of evaporating dampness. Soon all traces of the storm would be gone Sara noted with some satisfaction as she stood at the living room window watching a sparrow (her mother called them ‘little brown jobbies’) peck at something in the damp earth of the rose garden. From the warmth of her bed to the cool darkness of the rest of the house she now felt drawn to the sun, to get out and feel it on her face and arms. A bike ride would do.

Sara had no place to go in particular but after taking Bertie for his morning constitutional she put on a an old pair of corduroys pinched at the ankles by a pair of bike guards, and a hat to guard against the sun. The sky was very blue, washed clean of city soot, the kind of pleasing warmth against a sweater that felt almost like spring. She had a beach bike with thick tires and simple gears. The green paint had long since chipped away but Sara thought the harsh, changeable weather of the city and the constant wind coming off Lake Ontario full of acid rainwater made repainting it a waste of time.

She put her leather satchel in the big wire basket and pushed off, coasting slowly down the long driveway, feet grazing the pavement, thin scarf flying behind. Hands on the handlebars, she looked up and saw the friendlier clouds, the small white ones that had so often taken up her thoughts as she lay under the plumeria bush in the backyard. Her parents, who’d been to Hawaii once on a tour, had bought it home as a seedling and while made it through year after year of winter to grow spreading branches heavy with fragrant blossoms of yellow and cream, they’d told her often of their night at the luau in Wakiki when their host had threaded dozens of these flowers into leis which were put around their necks before the feast began. The way they described it, looking at each other, the pungent aroma that her mother said made her giddy and a little bit ‘fast’. She would laugh then, like Katherine Hepburn, looking heavenward, and her father would always blush.

The plumeria shouldn’t have survived in this cold climate but her mother bagged the huge bush in plastic every winter and then wrapped it in an extra layer of burlap. Then she sprayed a layer of water on it during the first hard frost in January and there it stayed, silent and sleeping, until April when the longer days and warmer weather gradually dried up outer covering and her mother would free it again. The neighbors declared it a marvel.

Sara had never been to Hawaii but her mother had once told her she was not so different from the plumeria. She’d come home from school one afternoon with scratches on her face and arms.

“What happened?” It was a rare day when Delys was home. She was usually down the street taking care of the neighbor’s children. Sara had fled directly into her room and refused to come out.

“My bangs aren’t straight!” was all that came muffled through the door after much pleading. When her mother found it unlocked an hour later Sara was sitting on the old wooden vanity, her hair sopping wet flattened under strips of scotch tape across her forehead. She was pressing her palms on her hair, smoothing it down and rocking back and forth.

“What happened!” her mother demanded again, taking her by the shoulders. Sara looked off into the mirror and saw everything in the backwards world. There were so many unexplainable things there. She didn’t understand, but it didn’t stop them from happening. Her mother’s cornsilk hair curled away from her face like a spent dandielion, ready to rise up into the air, like the rest of her. She was all soft and simple. A simpleton. She watched Sara with all the intensity she posessed and still it wasn’t enough to penetrate the density between them.

But she was waiting for an explanation.

“They took me to a closet.” The supply room at the school. The others thought she’d told her teacher about their glue sniffing marathons out by the gymnasium door. The Principal had come for them, there was blood to pay. The girls found a key, pushed her inside and held her up against the wall, clawing at her, stoned and enraged. She didn’t scream. When they were done they left, one by one and she had crept out after them and taken her place in English class as if nothing had happened. They filed in later, defiant and glaring at her. From now on she'd be labled as a snitch.

It was useless to tell her mother any more. She’d long ago stopped trying to cross the divide, to pluck at the strings of her mother’s heart. There were too many children vying for her attention and she’d always said Sara could take care of herself.

“Like water off a duck’s back,” Delys marveled to her friends. “I don’t worry about my Sara!” And then would come the darkness when she complained of the menial jobs she had to take to support them and her spendthrift husband.

But that day her mother had looked hard into her daughter’s eyes and sighed.

“You’re in trouble, aren’t you?” she asked. And she looked off for a while, still holding on to Sara in a protective fashion. Daughter leaned into mother and it was then Delys said,

“You aren’t so different than my plumeria.” Sara didn’t care what she was saying, so lost she was in the embrace. Her mother put her face close to Sara’s lank hair but stopped at putting a hand up to stroke it. “This isn’t your time, she said with resignation, “and you’ve got to cover yourself up and wait for summer to come.” It was then Sara realized just how much drudgery the delicate Hawaiian transplant had been, demanding her mother’s time without mercy, unrepentant. And only Sara to lie under it each flowering spring to breathe in its perfume and dream its dreams.

There was no traffic on the street, dappled as it was from the trees still heavy with fall foliage, the distance beckoned. She set out for unknown territory. Today would be an adventure!

But it was not to be. One turn led to another and she was on the street where Nate lived. She didn’t care if he lived or died. But the house was suddenly there and in the driveway sat a red pick-up truck.

Something new.

She parked her bike on the kickstand and unlatched her pant guards. Shaking out like a dog coming from the rain she made her way up the path and finding the door closed and locked this time, she knocked and waited for someone to let her in.

<< Home