2012, H1N1, and Being A Hero

The special effects in Roland Emmerich's film, 2012, are stunningly realistic - especially if you live in Los Angeles, which falls into the sea with spectacular crashing, popping, and upheaving sideways after the overheated earth's core causes something called 'earth crust displacement', where continents shift 1,000 miles all in one go. John Cusak, who plays a talented but struggling author of a novel with modest success, (hmmm...) is the everyman hero, a guy who saves his family when millions perish. We all would like to believe we're that guy, and not the crowds of hapless little figures seen in the long shots, falling off bridges, hanging on to toppling buildings, screaming helplessly all the way.

The debate to get the H1N1 vaccine doesn't reach the cataclysmic heights of a fissure swallowing up an entire city, but there are some similarities when it comes to when and how we listen to our inner voice when it comes to protecting our families. On one hand, the government has been predicting doomsday numbers when it comes to the death of healthy, young people, including those who weather the typical flu regularly. On the other, there are many, equally frightening rumors, stories, and press coverage of people who managed to get immunized and suffered mysterious, wasting diseases, or even died as a result.

When the vaccines began to arrive in the Americas, I was in Canada for a family wedding. Up there, for those of you who think Canadians are socialist-loving sheep who obey the government unquestioningly, we are, in fact, a nation of skeptics and independent souls only slightly left of our ancestors, the hardy fur trappers and bold immigrants who left hearth and home to brave the unknown in the wintry landscape of a northern giant. Yes, we are not generally risk takers who strive for the traditional American free enterprise model (I've worked for mine, so screw you if you're not smart enough to get yours), but we aren't our brother's keepers either, so you might say the Canadian relationship with the government is as rowdy and love/hate as you get. Just witness a typical day in Parliament, where several different elected minority groups who make up our House representatives duke it out over federal issues. Elephants and donkeys got nothing on us.

So most of what I heard up there about the coming immunizations, was nothing short of hysteria. Friends reared up with indignation and warned me the mercury (thermisol) in the vaccine would give Mimi autism; there was talk of the dangers of the augmented version being distributed due to lack of egg protein (squalene- shark oil) somehow linked to the American military and Gulf War Syndrome. Others told me the flu shot had actually caused the flu in their kids. Then there was the poo-poohing of the pandemic numbers, (and most people I talked to thought a pandemic was related to numbers of deaths, rather than numbers of countries involved). No one knew anyone who had died from H1N1, so these stories of deaths among children and young adults were felt to be vastly overstated.

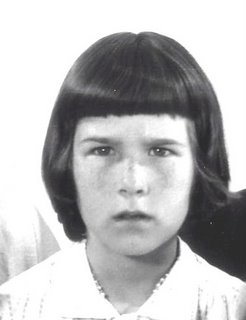

Back in the States, things were calmer, but not any clearer. The government, having promised to deliver enough vaccines for everyone by late fall, was starting to behave like the man behind the curtian in Oz. Bob and I had already decided to give Mimi the vaccine, but getting access to it became nigh on impossible. There was (and still isn't) a clear channel of public information outlining the distribution plan, schedule, and availability. We heard of the first clinic in Redondo Beach on a piece of paper stuck to the counter at Mimi's school. And at this one, panicked crowds of thousands from as far away as Santa Barbara lined up, and caused a virtual shutdown of the surrounding streets.

Although I was glad we hadn't been caught up in this madness, so began a slow, creeping anxiety centered on just how far I would go to protect my daughter. Visions of other circumstances in history began to coalesce. Would I have gotten out of London, as some did, during the plagues? Would I have survived the Great Flu Epidemic of 1918? My great-grandmother had nursed others through it, but she was so exhausted by the effort, she succumbed herself, something my grandmother was bitter about ever afterward. Would I have gotten out of Germany before WWII? Would I have packed my family into a car days before storm surges devastated New Orleans and drowned those left behind? I had always assumed I would, but it was just so much armchair quarterbacking with the gift of hindsight thrown in.

At what point was I willing to make the effort, as some had already, to wait in long lines, push ahead of others, scheme, fight, do what it took to ensure early access to the vaccine? I passed up several more clinics, playing a game of chicken in the hopes that Mimi wouldn't get the flu, wouldn't get it and die, or conversely, get the vaccine and be the one who came down with GBS, wasting away in a wheelchair. I still had a lot of questions about the type of vaccine we were getting, what the risk factors were, and we continued to weigh all the pros and cons.

But in the end I had to trust my instincts. Mimi has had the regular flu mist since she was a year old, with no effects. And enough thermisol in early immunizations in China to dispel any fears on that score. Yesterday we heard about a children-only clinic (which meant the mist rather than a shot, which Mimi prefers). There was only a small lineup, and the job was done within 3o minutes. No sooner was Mimi home than I heard from a friend the vaccine had just been delivered to the pediatrician's office, which meant I could have waited one more day and asked all the questions that were plaguing me. In the end, it came down to a little bit of panic and a little bit of logic. I can't say which side won out, only that it's done. And Mimi is fine - no after effects at all.

John Cusak's character in 2012 managed to avoid falling lava, cracks the size of Manhattan, tidal waves, and disappearing land masses to get his family on one of the four giant arks built by the nation's leaders to ensure the survival of a tiny percentage of the world's population. The guy had way more luck than brains, but his gritty courage and determination to survive is something we all want to believe in.

Real life, it seems, is a lot more complicated. And so are we.

<< Home