The DNA of Tarts

As part of my new path I have made and fulfilled a number of changes in my daily life and outlook. Thanks to Greg Drambour in Sedona, who gave me my list, I am nearly there. Just a couple more and I will have made my commitments. Feels very good.

On Saturday I joined the California Writer's Club, formed in 1909 by Jack London, and still active with 1800 members in a dozen or so locations. At my first meeting we met with a novelist and food writer and she gave us a few writing prompts. Now that I am putting in three days a week writing, these help to focus and begin the process. Writing about my food memories from childhood is easy:

On Saturday I joined the California Writer's Club, formed in 1909 by Jack London, and still active with 1800 members in a dozen or so locations. At my first meeting we met with a novelist and food writer and she gave us a few writing prompts. Now that I am putting in three days a week writing, these help to focus and begin the process. Writing about my food memories from childhood is easy:

The DNA of Tarts

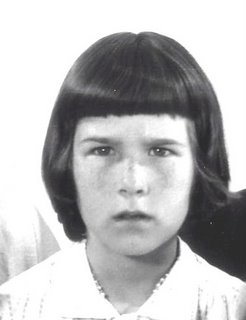

Butter tarts –they sat on a plate in Nana Northey’s oak refractory

table in the room that doubled as a living and dining room. She had chosen to use the adjoining, smaller

room as a parlor, a nod to her days as the daughter of a gentleman farmer in

Norfolk. In her childhood home there

were servants and most likely a morning room, a grand parlor, a library, a

snug, and a dining room that accommodated twenty guests. Here in her two-bedroom walk-up apartment

over a busy, unfashionable Toronto street, noisy with streetcars and vendors, she

had raised four girls, cots for each in one bedroom, the other reserved for her

and her second husband. I never went in

her room, it was always cloaked in half-shadow stillness, but from the door I

could see the fancy spread and collection of dolls she made clothes for.

Pastry tarts were the only dessert she made – and she made

them regularly. Butter, jam, and her homemade mince at Christmas. When we all

crowded in on these family gatherings, our cheeks red raw from the wind, father

left behind to find a parking space in the slushy, slippery cold, we headed

straight for her tarts, coats hastily flung on the nearest bed, and devoured

them with abandon, for she always made dozens.

They were little bowls of perfection. Flaky pastry cradled a

mixture of butter, eggs, cream and brown sugar, cooled and firm as these

confections were always served at room temperature. To try them straight out of the oven was like

putting boiling napalm into your mouth and so she made them the day before and

stored them in Queen Elizabeth Commemorative tins, layered with wax paper. Never runny, never adulterated with corn

syrup as some did, the filling with its frothy top had a gooey texture stayed

in your mouth so you could savor the caramelized sugar mixed with subtle, rich

hints of butter and cream. Bits of pastry always stayed on your lips to be

licked off later, and after the filling had all been devoured, there was a

small crescent of pastry left to savor before all that was left was the memory.

Her tarts were made weekly, waiting for whenever we visited,

later as students when we came to see her in her new, modern efficiency model

on the 10th floor of a highrise for seniors. They sat on a china plate next to a pot of

steaming, Red Rose tea, cups and saucers mixed together in a riot of flowery

patterns. These tarts were the

conversation starters, opening the way for a landscape of troubles, curiosities

(such as the discussion about why our small breasts were so much easier to live

with than the kind that flopped about in bed and necessitated a bra for

comfort) and stories of England. Nana’s

stories were as exciting as our own lives, filled with WWI romances, punting on

the Thames, ardent soldiers returning from battle, the loss of her mother in

the Great Flu Epidemic, her father’s humor and playfulness, all a world away

from our Canadian lives. She told us she

had run away with our grandfather, a mysterious man who ran an acting school

where they landed in Montreal, who was perhaps a Communist, union organizer,

flim-flam man, cheater of epic proportions, and long, long gone. He had disappeared during the Second World War,

and we only heard later that perhaps he had not actually gone to fight but to

take up with another woman whom he called his wife. I believe Nana was still a little bit in love

with him, certainly she never spoke ill of him, the fuller picture came out in

bits and bobs from my mother, who remembered sharp and tender moments all on

the same path, but for whom she only came to miss much later in her life when only

the softer moments remained. The wounds from a fractured life my mother

dismissed more and more as time went on, transformed into legends of her

mother’s bravery and stoicism in the face of poverty and disillusionment.

Though buried beneath admiration for the parent left behind, the scars remained,

bitter tracings through a life fraught with demons and ghosts. What remained

though, was my mother’s love of pies, and though nearly blind and without a

working oven, she still makes them with the same vigor and purpose as the women

before her.

The raspberry jam and butter tarts were my Nana’s welcoming,

they spoke of the old country, her roots, which were never nostalgic because

she had made her break with her family and seemed more rooted in her new home

despite the financial hardships and the loss of a widowed father she clearly

adored. Too proud to let him know he had

been right, she never went back to England, and I am left wondering just how

much he knew and for how long. This charismatic

and mysterious man she had stolen from her older sister’s embrace, the

illegitimate son of a washer woman, a Jewish refugee from the European pogroms,

the one who had enticed his bride to abandon everything she knew, bestowing on

us unknown remnants of a history we live through the tangled web of DNA that

directs our futures, even now.

We choose the memories that sustain the woman who gave us

our start in the wandering world, who gave us her version of chance and pride

and resilience. We are hers, and she was

ours.